There's a pattern I've noticed in how systems fail. It's rarely the dramatic moment everyone imagines—the whistleblower, the exposé, the sudden regulatory crackdown. Instead, it's something quieter: a settlement agreement, a shift in legal interpretation, a case that seems narrow but reveals structural problems that were always there, waiting.

The Cognism privacy class action settlement is one of those moments.

On its surface, this is a story about one company and how it allegedly allowed free-trial users to view contact information of people who never signed up for the service. Cognism denies wrongdoing. They settled anyway. But if you zoom out—and I think we need to zoom out here—what you're really seeing is the first serious stress test of an entire business model that underpins modern B2B marketing.

The Product-Led Growth Paradox

Let me start with something that sounds good in theory: product-led growth. The idea is elegant. Instead of gating everything behind sales calls and enterprise contracts, you let people try your product. You reduce friction. You turn software into a self-serve experience. Free trials become your best salespeople.

This works beautifully when your product is, say, project management software or a design tool. But what happens when the product itself is other people's data?

That's where the model gets complicated. Because now you're not just reducing friction for your users—you're creating it for people who never opted in to be part of your product in the first place. Their names, their emails, their job titles, their phone numbers: all of this becomes the substance of someone else's free trial.

The legal theory emerging from the Cognism case is straightforward, even if its implications aren't: when you display personal data to users—even free users, even trial users—you're making a claim about your right to process that data. And if you can't prove consent, that claim can be challenged.

The Consent Fiction We've All Been Living With

Here's what I think is the deeper issue, the thing that makes this case a canary rather than an anomaly: the consent model in B2B data has always been more fiction than fact.

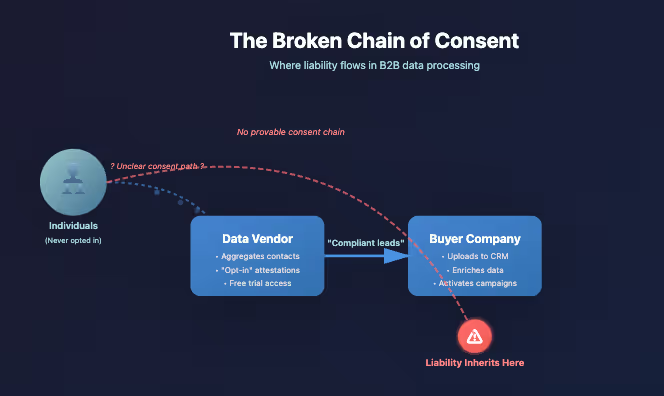

Walk through the typical content syndication flow with me. A marketing team wants leads, so they pay a vendor. That vendor delivers names and emails, stamped as "opt-in." The marketing team assumes—because what else can they do?—that somewhere, somehow, these people consented. Maybe they downloaded a whitepaper. Maybe they attended a webinar. Maybe they checked a box.

But here's what actually happened: The person filled out a form on a third-party site. That site had language—buried in the fine print, if it was there at all—that their information would be shared with "partners." The person never visited your landing page. Never saw your brand. Never made an affirmative choice about whether they wanted to hear from you.

And yet, legally, once you upload that lead into your CRM, enrich it, email it, route it to sales, retarget it with ads—you become the processor of record. Not the vendor. You.

This is the uncomfortable asymmetry at the heart of the B2B data economy: vendors sell on the promise of compliance, but buyers inherit the liability.

Why This Problem Is Getting Worse, Not Better

The Cognism settlement spans multiple states. That's not an accident. We're in the middle of a privacy law proliferation at the state level. California passed its Consumer Privacy Act. Virginia followed. Colorado, Connecticut, Utah—the list keeps growing. Each new law expands definitions, lowers standing requirements, and creates more venues for plaintiffs to bring claims.

What you're seeing is the legal landscape catching up to what the technology has been doing for years: processing personal data at scale, often with consent chains so opaque that no one can confidently say where the authorization originated.

The economics of litigation are shifting too. Class actions become more attractive when there are cash settlements available, when discovery can expose systematic practices rather than isolated incidents, when one weak workflow can scale into thousands of affected individuals.

This isn't GDPR panic. This is something arguably more destabilizing: U.S. plaintiffs with financial incentives and increasingly friendly legal venues.

The Question Underneath the Question

So here's what I keep coming back to: What does accountability actually look like in a system this complex?

When a lead enters your database, can you prove—not with a vendor attestation, not with a PDF of terms and conditions, but with actual evidence—that this specific person consented to this specific use of their data? Can you show they reached the page, saw the language, took the action, authorized the processing?

For most B2B marketing teams right now, the honest answer is no. And that's not because they're careless or unethical. It's because the infrastructure for verifiable consent doesn't exist yet. The systems aren't built for it. The incentives don't reward it. The entire supply chain operates on trust and legal indemnification clauses that may not hold up under scrutiny.

What Comes Next

I don't think this is the end of B2B data. But I do think we're watching the end of unprovable consent as a viable business practice.

The next generation of data platforms will need to be built differently. Not just compliant by assertion, but auditable by design. Event-level proof of consent. Verifiable user journeys. Buyer-specific authorization trails. Suppression-first enrichment—where you validate before you activate, not after.

This is, in many ways, a better system. More transparent. More respectful of individual agency. But it's also more expensive, more complex, and more restrictive. Which means it will require not just better technology, but a fundamental rethinking of how demand generation operates.

The Cognism case won't be the last of its kind. It's probably not even the most important. But it's a signal—a clear one—that the legal and ethical assumptions underlying B2B data have become untenable.

The question now is whether the industry adapts before more settlements force the issue, or whether we're going to learn these lessons one class action at a time.

I suspect I know which way this goes. But I'd love to be wrong.